The power of purpose has been widely covered, but far less has been written about its pitfalls.

There’s no question that we all, as consumers and businesses, can be motivated and inspired by a noble or aspirational purpose. As human beings we all find extra energy and drive to act when we feel our actions can help us to achieve aims that are meaningful and important to us. The janitor at NASA does his best work when he feels he’s helping put a man on the moon.

This motivational power of “purpose” has been successfully applied in a wide array of businesses to galvanize and inspire employees (strengthening loyalty, productivity and performance) and to propel consumer passion for products and services (growing revenues and market share).

But there are countless failures and missteps that must also be acknowledged. And extreme care must be taken to ensure that the “purpose” we embrace and assign to our businesses and brands is authentic, relevant, and deeply rooted in the essential role our businesses and brands play in the lives of our constituents.

The relevance dimension is of utmost importance and where most failures occur.

In the case of Unilever, CEO Alan Jope had solid evidence in the performance of brands like Dove and Omo over many years, that a relevant purpose, deeply rooted in the product’s role in consumers’ lives, can have meaningful motivational firepower in the marketing of these brands. For Dove, a basic soap, hair, and skin-care brand to embrace a purpose of empowering women to reject the unachievable beauty standards disseminated by the cosmetic and fashion industries — and instead to embrace their “real beauty” — was highly relevant, true to the product’s delivery and role (essentially cleansing), and a compelling basis for brand choice in largely undifferentiated categories. The same can be said for Omo’s support of messy play for kids (we’ll clean their clothes…so go ahead and encourage them to play in the mud). But where Jope went astray was in declaring that no Unilever brand could live without a higher purpose. Not because this wasn’t a worthy aim, but because he hadn’t anticipated the over-exuberance with which his rank-and-file marketers around the world would act on his encouragement. Worse yet, he then backpedaled when talking to a dissatisfied investor community and effectively came across (even to his own people) as lacking in conviction.

Fundamental rigor around discovering and leveraging each brand’s authentic and relevant purpose is a high-level discipline that few will get right all the time. Jope’s team has actually gotten more of these right than most others have.

Gillette had, for many years, grounded its marketing to men with a product-performance (and also aspirational) positioning as “The Best a Man Can Get.” A brilliant slogan that spoke simultaneously to the performance of its products and the aspirations of its users. Compelling, motivating and highly relevant stuff. Yet in January 2019, the team at Gillette decided that its higher purpose might be to redefine masculinity and discourage those dimensions that tended toward misogyny or bullying. These were noble aims, of course, but wholly and completely disconnected from Gillette’s role in its consumers’ lives. Their “Best a Man Can Be” campaign fell flat with their users, as Gillette should have anticipated it would. Worse yet, their execution came off as actively critical of their consumer, admonishing them for their toxic tendencies. Not the most inspiring or attractive posture for any marketer to take with the folks they hope to engage in their brand. One word changed in the slogan. But what might have seemed to the team as a natural extension, the move from “get” to “be” actually detached the brand from its product-performance moorings and relevant aspiration. “I’m at my best when I look and feel great” is an aspiration that Gillette can credibly help its consumers to achieve. But “I can be a better person” is decidedly not. (Gillette quickly recognized its error in the face of significant share losses and smartly reversed course).

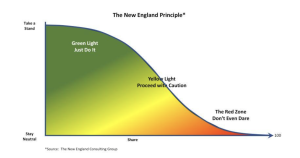

The biggest hazards in defining a brand’s purpose are those of over-reach. And determining where the line is can be challenging. You can see how the Gillette team at P&G might have gone from one dimension of self-improvement to another, feeling confident that they were well-grounded in the Brand’s DNA. But they weren’t. They crossed the line, and it hurt.

Pepsi famously ran headlong into over-reach with their Kendall Jenner ad in April 2017. They made the ad in-house without the participation of an outside agency (and the relative objectivity such participation might have brought to the process). And a team of otherwise capable marketers didn’t just cross the line, they leapt over it. Of course, Pepsi can help bring people together. And of course, a kind gesture (like offering someone a cold, delicious Pepsi) can help to diffuse tensions. But the kind of tension they depicted between protesters and a police force? Seriously?!

When diagnosing how this sort of over-reach can happen — how talented, capable marketing teams (like those at Unilever, P&G and PepsiCo) can make such colossal mistakes — consider the power of purpose. It’s alluring. Magnetic. All-consuming. And the very teams charged with inventing and activating a brand’s purpose are, themselves, susceptible to this extraordinary power. Fully entranced, they may cast aside their intelligence and know-how — their discipline and rigor — drawn like moths to the very flame they’ve created. This phenomenon, in the end, is what Alan Jope at Unilever failed to appreciate.

As more and more businesses of all kinds seek to leverage the undeniable power of purpose, it will be increasingly important to mind the pitfalls, and to provide our teams with disciplined guardrails and expert guidance; so that they might control the very power they’re aiming to unleash.